Alleghany

Angels Camp

Coloma

Columbia

Dutch Flat

Folsom

Foresthill

Grass Valley

Hammonton

Iowa Hill

Jackson - Plymouth

La Porte

Nevada City

Placerville

Poker Flat

Auburn History

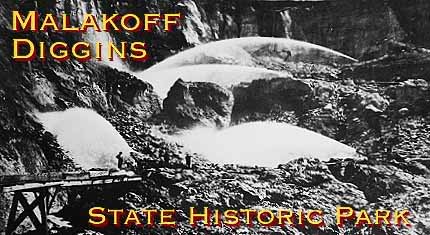

Gold Districts - Malakoff

|

While it may indeed look romantic in the moonlight, the glare of the noonday sun reveals the canyon for what it really is: a mining pit that caused environmental devastation on such a large scale that even now, almost 15 decades after the first hillsides were blasted away, the scars are still raw and blazing. At Malakoff, the easy-to-find surface gold played out during the first couple of years of the Gold Rush. But the deep, stratified sediments overlying bedrock in the region were found to be full of gold -- not in the form of nuggets or veins, but in fine particles that were difficult to extract by traditional methods. "The gold in the sediments was almost

dust, which didn't lend itself to hard rock or placer techniques,"

Clark explained. "They had to be careful -- sometimes whole hillsides would slide off and there'd be guys buried," Clark said. The tailings -- muddy water, rock and whatever else washed down -- were discharged from the sluice boxes directly into area streams, which soon became clogged with silt and debris. Extensive downstream flooding resulted. In Marysville, silt from Malakoff Diggins actually raised the bed of the Yuba River higher than the level of the city. The free-for-all at Malakoff continued until

1884, when Judge Lorenzo Sawyer in effect halted the practice of hydraulic

mining with a permanent injunction against dumping tailings into the state's

waterways. But there's lots more to see. For most visitors, the main focus is the ghostly remains of North Bloomfield, a once-lively town of 1,500 that served as a supply base for the Diggins. About a block of buildings, some dating to the 1850s, have been restored or re-created to give a feel for the Gold Rush days. White picket fences give the quiet street the air of a small Midwest town. One of the buildings houses park headquarters and a museum whose artifacts include an oversized sewing machine used to make hoses for the mining operation, and model showing how hydraulics worked. In summer, park rangers lead tours through a general store stocked with 19th century merchandise, a furnished home from the Gold Rush days and a drugstore whose shelves are lined with bottles, boxes and vials of patent medicines. "The druggist lived in a room in back of the store because then, as now, people would sometimes break in to steal the drugs," Clark pointed out as he showed a visitor around earlier this month. "Of course, anybody back then could call himself a druggist -- as long as he had the drugs." A church, schoolhouse and other buildings complete the basic sightseeing rounds. Visitors who get a case of gold fever during their explorations can check out a gold pan (free) at park headquarters and try their luck in Humbug Creek -- humbug, Clark said, being a term for a place where the gold has played out. Which, ironically, it hasn't: "We take

people to a place downstream that's very popular, and usually they find

something," said Clark. As for the Diggins themselves: "Well,"

said the ranger, "there's more gold still there than ever came out." Park facilities include hiking trails, picnic grounds, a 30-site campground and three rustic cabins accommodating four campers each. Swimming and fishing are available at Blair Pond within the park. The biggest event of the year is the June 13 Humbug Days celebration, which features volunteers and docents in period dress, live bluegrass entertainment, crafts, a gold nugget race, a parade, concession stand and more. For more information, call (530) 265-2740. |

When

visitors to Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park inquire about where to

find the best views, supervising ranger Larry Clark directs them to a

lookout point in the Chute Hill campground." You come out here in the

moonlight, and it's all white reflections out there. You can hear the

frogs croaking, the bears snorting, the coyotes yelping. . . it's really

something, especially during a full moon." The view of which Clark

speaks is of a kind of mini-Grand Canyon with dramatically pleated walls

of brightly colored sediments. The "canyon" is 7,000 feet long,

as much as 3,000 feet wide, and nearly 600 feet deep in places.

When

visitors to Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park inquire about where to

find the best views, supervising ranger Larry Clark directs them to a

lookout point in the Chute Hill campground." You come out here in the

moonlight, and it's all white reflections out there. You can hear the

frogs croaking, the bears snorting, the coyotes yelping. . . it's really

something, especially during a full moon." The view of which Clark

speaks is of a kind of mini-Grand Canyon with dramatically pleated walls

of brightly colored sediments. The "canyon" is 7,000 feet long,

as much as 3,000 feet wide, and nearly 600 feet deep in places.

While

beautiful in its own way, the Malakoff mine pit is a testimony to the

avarice that was part and parcel of the Gold Rush and to one of

the nation's first environmental-protection measures.

While

beautiful in its own way, the Malakoff mine pit is a testimony to the

avarice that was part and parcel of the Gold Rush and to one of

the nation's first environmental-protection measures.

It didn't take long to devise a new method of extraction: In 1852, hydraulic

mining was invented. The technique utilized cannon like nozzles, called

monitors, to wash away the gold-bearing hills with high-pressure blasts

of water. Elaborate systems of reservoirs, ditches and sluices were created

to bring water to the site. Mud washed from the hillsides was channeled

through sluice boxes that caught the particles of gold.

It didn't take long to devise a new method of extraction: In 1852, hydraulic

mining was invented. The technique utilized cannon like nozzles, called

monitors, to wash away the gold-bearing hills with high-pressure blasts

of water. Elaborate systems of reservoirs, ditches and sluices were created

to bring water to the site. Mud washed from the hillsides was channeled

through sluice boxes that caught the particles of gold.

Today's visitors to the 3,000-acre state park can hike on miles of trails

that lead through the colorful pit, where rusting monitors and cables

litter the surreally sculpted landscape. Those who come prepared can venture,

during the dry summer months, into the 556-foot-long Hiller Tunnel, through

which water for the mining operation once flowed.

Today's visitors to the 3,000-acre state park can hike on miles of trails

that lead through the colorful pit, where rusting monitors and cables

litter the surreally sculpted landscape. Those who come prepared can venture,

during the dry summer months, into the 556-foot-long Hiller Tunnel, through

which water for the mining operation once flowed.

KNOW

BEFORE YOU GO:

KNOW

BEFORE YOU GO: